When we spoke in April last year, I told you I had left tech to join a restaurant, pivoted it online, and was now “finding our place in that (new) normal”. I was both new to the service industry, and to Toronto (and still am!). Three months later, you probably saw me on Business Insider packing meals (and still criticizing US immigration policies). Ironically, that was also our last service; unable to grow, struggling to sustain, we shutdown on July 7th, 2020.

Here’s what happened in those three months, and what we can all learn from it.

The first week online was encouraging. We sold way more than we expected. $1279.90, to be precise. Quick reminder: we accepted orders online throughout the week, but only cooked once a week. Almost all of the orders came from friends and family, who were happy to support once, but it had to feel ‘worth it’ for them to re-order, let alone spread the word. We got mixed feedback; the chicken tikka masala was good, the quantities were great, but there was too much rice, no bread, (naan? roti?) no salad, and the rajma (kidney beans) gave them gas. As expected, the next week we did a measly $401.25, and the feedback wasn’t much different.

We had essentially taken our ‘offline’ product offering, and put it online. We hadn’t tweaked the product, not given any thought to packaging, the pricing was still the same, the positioning was unclear, and we didn’t really understand who was ordering online, and why. The only thing we had gotten right, it seemed, was to offer a bundle that was easy to order and kept you going for a week.

I could see the current model wasn’t going to work, but what all do we change?

In the two months I spent at the takeout joint downtown before we shut it down, I learned one thing: whatever we were selling was selling, but we didn’t have product-market fit.

On one hand, our products were underpriced for the quality they packed, squeezing margins to a minimum (and no VC $$$ to pay the bills). We struggled to raise prices because, as bad as it sounds, customers don’t ‘expect’ much from a takeout joint, and, hence, don’t like to pay much. On the other hand, despite the bang for the buck, we still didn’t sell too much! Whoever had our food, loved it, but the word- of-mouth loop wasn’t closing fast enough. It almost felt like we were barking up the wrong tree.

Our audience had been predominantly desi (South Asian) or, bear with me, ‘brown’. These are South Asian immigrants (like myself) who mostly eat South Asian food, have South Asian friends, travel ‘home’ every year, and still compare things to ‘back home’, especially the food. They may be FOTB, or have been here for years; it doesn’t matter. Regardless of the quality, they will most likely not spend more than $10 on South Asian food, and certainly not at a dhaba (kiosk).

Why am I profiling so blatantly? Let me explain.

When you’re running a restaurant (or any other business), you have to understand who’s your customer, and who’s ‘not’ your customer. Why? Because you primarily want to offer what ‘your’ customer wants, and little else. Your marketing is targeted at them, the offering is tailored for them, the pricing works for them, the product suits them, the experience tickles them, and the thought of coming back excites them. Anyone who’s not your ideal customer is quite likely to be disappointed and you only want good vibes (and reviews). Tech companies like Airbnb, for instance, focus heavily on optimizing for their high-expectation customer, or HXC, because “if your product exceeds their expectations, it can meet everyone else’s.”

In order to determine who should be our HXC, and who shouldn’t be, I spoke with over a hundred people in Toronto. Not all of them were customers; many were networking connections (courtesy Lunchclub and TechTO), and became customers later. I was looking to understand who they are, where they spent money, how much they spent, and why.

The colour of your skin, as it turns out, is a good proxy for your food choices, but your world view defines how much you value them.

I have conveniently bucketed all ‘non-brown’ folks into ‘white’, and that may not seem fair. It’s only for simplicity’s sake. Compared to anyone else, brown people, like everyone else, feel differently about their ‘own food’. Also, when I say brown, I’m referring primarily to Pakistanis, north Indians, and Kashmiris; south Indian and Bengali food is quite different, let alone Middle Eastern. Why do I keep saying brown, and not desi? ‘Brown-brown’ sounds better than ‘desi-desi’. 🤷

‘Brown-white’, like brown-brown, are South Asian at heart; they may be immigrants themselves, or have immigrant parents (maybe living in Begumpura). They’ve grown up eating South Asian food, still absolutely enjoy it, but also readily enjoy other cuisines (and even cook them at home). On occasion, they will spend upwards of $25 per head on a food experience, especially if it’s ‘insta worthy’. On a night out with non-brown friends, they will likely spend more. Coconut? Guilty as charged.

‘White-brown’, on the other hand, are not immigrants, at least not from South Asia. Instead, they are the well travelled, yoga flexing, local business supporting, woke, young individuals and (potentially interracial) couples. They have had South Asian food many times, can decipher CTM, and will surely pay for a wholesome culinary experience. Their kids grow up to be global citizens, well versed in tikkas, kimchi and tacos.

Unlike them, ‘white-white’ are (mostly) ‘ for immigration’, know we exist, may have had CTM on a rare ethnic excursion, but on a spice scale of 1 to 10, choose 0. They do have (and spend) the most $$$.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not saying brown-brown people are not worth serving. In fact, I strongly believe that each of those groups is worth serving. However, one restaurant, can most likely not delight each of those groups without disappointing all of them in some way. In fact, for a delivery-only restaurant in a post-COVID world, it’s even more important for its customers to have the right expectations because, once the food is shipped, it’s not coming back.

Knowing your customer isn’t enough; you also must consider what ‘ jobs’ they want done, and then decide if it’s something you want to do for them.

The Survival Kit was our best-selling item the first two months. Four (or eight) healthy servings of meat and vegetable curries, a wholesome salad, two different sides, and a dessert. White-brown, especially those trying us for the first time, liked the ease of not having to choose individual items. Brown-white loved the taste, were pleasantly surprised by the quantities, but didn’t quite appreciate some of the curries. Brown-brown saw it as a better-tasting, more expensive, ‘auntie’ ‘meal delivery’-alternative.

They all liked it, but it was doing a different job for each persona.

For white-brown, Tuesdays (when we delivered) became ‘Indian night’; the Survival Kit worked well to feed a family of four, and the kids. Brown-white only ordered the Survival Kit if they hadn’t had desi food in a while and were ready to commit. Brown-brown had no such qualms; they ordered regularly and, as expected, were soon complaining that the dishes had become monotonous and should be cycled. “Auntie!”

Since we were doing different jobs for them, each persona viewed us differently, and expected different messaging, pricing, offering, packaging, service, and even billing for the Survival Kit. On top of that, bundling made it harder to get feedback about individual items (which hardly anyone ordered) and our learning plateaued.

Conflicting feedback and ideas were pulling us in different directions. It was time to decide: do we want to become a meal delivery (or plan) service, or continue to offer a restaurant-esque menu?

Meal delivery services that bring ready-to-eat meals to your doorstep every week have been around for a while. Traditionally, such meal plans had been the domain of suburban ‘aunties’, accepting orders over text messages, preparing standard home-style food, packing it up in plastic containers, stuffed in plastic bags, ferried downtown by their boys every weekend. If you wanted fresh food everyday, you could opt instead for a tiffin service that will deliver individual meals for a small fee. For somewhat better quality (and higher price), you could even subscribe with a restaurant looking to monetize off-peak hours.

In the last few years (before COVID), given the potential, commercial vendors stepped in and setup dedicated dark kitchens. Some specialized in halal, some healthy; eventually, like fintech, everybody started doing everything. But, still, they weren’t doing too well, not growing too quickly. Until 2020.

COVID-induced ‘work from home’ put meal delivery centerstage. The footfall that restaurants lost, (to some extent) they gained. The takeout orders that restaurants lost, they gained. The mindshare that restaurants lost, they gained. The space has grown so much by now that you can even get plant-based, gluten-free, organic… you get the drift. Grocery chains, not content with the killing they were already making, saw the trend as well, doubled down on ready-to-eat meals (both frozen and fresh), meal kits (ready-to-make), and, in a bid to “ support local restaurants”, even offered them their delivery channel. Amazon, much?

If you’re wondering why we didn’t do that, I’ll explain.

I saw ourselves as “The Charcoal Grill”, a restaurant brand. Granted, we were temporarily restaurant-less, and nobody knew for how long things were going to stay this way, but it remained a question of when, not if. In fact, I didn’t even mind our low volumes at the time. I felt that this was our opportunity to do R&D for a restaurant without the pressures of running two services, six days a week, and making payroll. Zubair initially disagreed; he saw where the industry was going, and leaned towards following along. But, I was clear and adamant; I didn’t want to be another meal delivery service, operating a factory producing sub-par food at volume. I still wanted to deliver a quality food experience, albeit at-home, and was confident that we could figure out another niche for ourselves and compete on value, not price or quantity.

It wasn’t an easy decision. It took plenty of research and long phone calls with Zubair but we eventually agreed: we will change, but, whatever choices we make, whatever path we choose, must have a line of sight to the restaurant we will (re)open one day (soon). The Survival Kit won’t take us there, and had to go.

Getting your menu right is hard. In fact, menu engineering, as it’s known, is a field in itself, and has many parallels with product strategy. It cuts across accounting (COGS), marketing (pricing), design (layout) and psychology (call-to-action). The aim is twofold: make you buy, and make you spend more. That’s why Starbucks won’t tell you about the ‘ short size’.

Before the pandemic forced us to close shop, I had reconfigured the menu for the takeout kiosk. Low margin options were eliminated, high margin options were elevated, prices were raised slightly (and ended in ‘.95’), and the categories were simplified. Other than a few pissed off old-timers, most customers seemed to appreciate the new look and weekly revenue inched up. (Summer was to be the real test but alas.)

Compared to a physical outlet (with a printed menu, mounted on a signboard), making changes online is much easier and cheaper. We began tinkering from the get-go.

The first week online, we added Kashmiri Hareesa. Zubair had always wanted to offer it, but it took a long time and effort to make (hard to do regularly), the logistics of serving with a sizzle were too much for a small kiosk, and you needed to have it with naan (which we didn’t serve). Online, it was a different story. White-brown folks who had tried it at the food tasting (for the new restaurant) excitedly ordered and a loyal fanbase began to develop. Given the premium nature of the product, we priced it much higher than what catering customers were used to being charged; they complained at first, but many among them eventually ordered anyway. The same story repeated with Mirchi Qorma, another Kashmiri special. We slid left on the demand curve, proving there is room higher up in the market for Kashmiri food.

Chicken Tikka Tacos was another hit among brown-white and white-brown; unfortunately, brown-brown didn’t quite appreciate the form factor. They insisted we bring back the Beef Short Ribs Sandwich. The bakery that supplied us Italian buns had shut down but we found a better alternative. I didn’t mind picking them up every Tuesday morning because who doesn’t like walking into a bakery and smelling freshly baked bread?

Rajma Chawal (black beans with rice) is a Kashmiri (and generally brown-brown) staple. At the kiosk, ten minutes before closing time, young brown-brown professionals and students would come running to pickup a box for dinner. It was such a set pattern that Zubair would start warming up the rajma a few minutes before. Online, it was a different story. No matter how we positioned it, brown-white and white-brown didn’t quite get the hang of it. It forced us to try something else, and that’s how we found an unlikely winner: Daal Fry. Like the hareesa, Zubair would give it a sizzle and hearts would melt.

If you’re wondering why I haven’t mentioned Chicken Biryani, the crown jewel of desi food, it’s because, for the longest time, we weren’t sure if we should do it. As a Punjabi, I certainly recognize its place and cultural significance. However, Zubair is Kashmiri, and makes incredible Kashmiri food, which is what we wanted to showcase to the world. Instead of offering the typical South Asian menu, our philosophy had been to offer Pakistani regulars, punctuated with Kashmiri specials. Sadly, that wasn’t working. People tend to play safe when ordering online, and having never tasted these Kashmiri specials before, they weren’t a popular choice.

Yet, it wasn’t until a conversation with a young, Asian, Mississauga-resident in early May that I realized all this. It was just another networking call. She had shown interest in the restaurant so I sent her a link to our menu. Her immediate reaction: “Oh, you don’t have Chicken Biryani?”

Of course, it turned out to be our biggest hit. People loved it, raved about it, and Minahil (my wife) would be very happy whenever I brought leftovers home. We even bundled it up with an order of tacos, and two cups of Masala Chai for a fun ‘ Desi Night’; only brown-white got it.

Our food was top-notch, the reviews were stellar, but we basically failed to get the word out quickly enough.

The online world is so muted. You can’t make eye contact with a customer walking by, encouraging them to engage. They can’t see others queued up for their orders. The smell of grilled meat can’t draw them in. Hearing others enjoying a good meal can’t entice them. And, if you’re new, they’ll probably never know how good your food is because you can’t sample.

On the internet, it’s you and a million others, religiously dishing out eye candy on Instagram, all claiming to be it. We had to try.

By the end of it, we had won 950 followers, and most posts fetched about 40–50 likes, but you could attribute hardly any actual orders to those likes. I thought we needed to increase our exposure, so I began spending $10–20 to promote some posts; the best looking ones fetched over 200 likes, but still barely moved the revenue dial.

That’s when I discovered ‘influencers’. These are (mostly) young, hip, Insta-savvy folks with a dedicated following on Instagram, the size of which — nano, micro, macro, and mega — determines their influence, and price. If you’re a restaurant, food bloggers will come to you, take attractive pictures of your food with all kinds of angles, pair them with the right catch phrase and hashtags, and post them as a story (less $) or post (more $) from their account. If you can’t afford to pay (like us), some nano and smaller micros will post stories as a ‘ collaboration’ for free food. These collaborations certainly got us some likes, but never really brought new revenue. Turns out, people who discover restaurants through food bloggers are more interested in trying out the next new thing, instead of coming back for more. Good luck explaining that to a self-proclaimed influencer asking for free food. We had better luck with lifestyle bloggers who post about a bunch of everyday stuff, not just food, and, hence, their audience is more likely to actually follow their advice and try you out.

COVID generally made it harder for homebound influencers to produce new content but, among them, one category thrived: celebrity chefs, putting out helpful content (recipes, tips, etc.). Collaborations with this category resulted in virtually no sales, but the most number of new followers; they probably followed us for more cooking inspiration!

Nobody likes ads, but they sure love a good story, especially one that’s close to home.

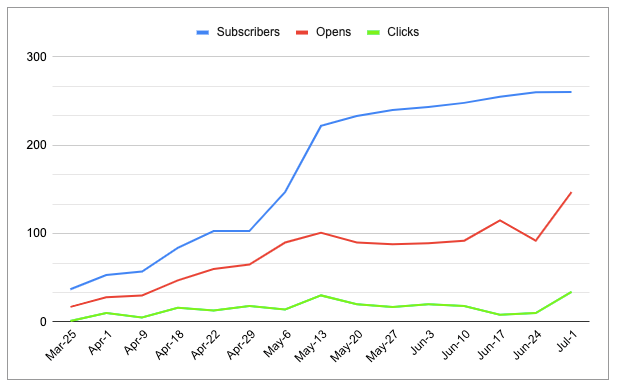

We had collected email addresses of our food tasting attendees so we could inform them of future pre-launch events. Instead, on March 26th, those 37 attendees became the first recipients of our newsletter, titled “Restaurants in the time of #Corona”. 17 opened the email (46% open rate), and 1 clicked and ordered (the rest came through WhatsApp). Next week, 58 received it, including those who had ordered the previous week; 28 opened the email (52%), 10 clicked, and a few ordered. I realized we were on to something.

I personally hate newsletters from retailers. They’re always looking to hook me into purchasing something I don’t need… and they’re almost never interesting to read.

The trick, as I realized, was to take people along on the journey. Like myself, many people have imagined running a restaurant or cafe of their own, but have no idea what it’s like. This weekly newsletter became their backstage access pass. They knew why we gave up the downtown location, and where we moved next. They got first dibs on hareesa, and our (attempted) subscription offering. There was taco humour, and biryani splendour. At ten weeks, I did a retrospective check-in (which I also shared on LinkedIn).

Even if they weren’t ordering that often, our audience still seemed to appreciate the updates (as seen by the growing subscriber base, and the rather consistent open rate). Despite having never written regularly, I, too, had begun to enjoy the weekly ritual.

Ergo, it was with a heavy heart, that I sent out the final update on July 5th, titled “Last Hurrah”:

Its summer — you’d rather go out, than order in, eh?

We get it. The world is beginning to feel normal again. You’d rather be out there on the patios, in the parks, at the beaches, soaking it all in. We, unfortunately, don’t have our downtown spot anymore so can’t give you that. Hence, we’ve decide to call it quits (for a while). There’s been a big dip in orders already and we foresee the trend continuing for the rest of summer. ’tis, what it ‘tis.

The orders grew week-on-week till early June. Our story was resonating, the response from customers was encouraging, and the community (and press) had been quite supportive.

But, it was also the time, when, for a while, it seemed like there was no more COVID.

With barely any new cases, Toronto entered ‘ Stage 2’ of COVID-19 restrictions. Restaurants and bars were allowed to reopen, and people thronged the beaches, pools, museums, and parks. Needless to say, at that time, everyone, including myself, was tired of being locked up inside and just wanted to be out and about, soaking up the sun. There were only a few months of summer left, and it had to be enjoyed before the ‘ second wave’ came knocking.

That’s when I realized food delivery in Toronto is an anti-cyclical business. We did well during the lockdown, and would probably do well again come winter, but without a storefront, there was no way to be competitive in the summer.

The fact that we weren’t on any of the delivery platforms hurt us quite a bit.

We couldn’t afford to pay the 30% commission (which the gov is now trying to cap), but we also couldn’t really use them because we needed orders in advance (because of our tight production window) and none of the platforms offered that. According to a downtown-based, young, black sales guy I spoke to in May, millenials do “discover” restaurants on Instagram and Facebook, but that’s not where they go when they actually want to eat. They used to open Google Maps to look for a place (they had discovered in the past) nearby, or wherever they were headed, but now their medium of “access” is a delivery platform like Uber Eats. Of course, in order to be a prominent choice on that, you will have to advertise (over and above the commission). There’s that, and then there’s us, asking customers to head over to our website to order directly (days in advance); not quite millenial-friendly.

Yet, we still managed to survive, albeit just a little bit longer, thanks to a health-worker.

In early May, a nurse from a local hospital reached out (on Instagram) asking if we were donating meals for health-workers. At the time, many restaurants were already doing it, but, firstly, we weren’t quite sure who, and how, to help, and secondly, we couldn’t afford to do it anyway. The nurse’s message solved the former; for the latter, I wrote to our customers, and posted online ( here and here). The ask was simple: go to our website, select the number of meals you would like to donate, and we will cook and deliver them at cost ($10). Once delivered, you would get an email.

The nurse had asked for 20 meals. I remember telling her about the donation drive, and that I’ll get back to her if we managed to raise the money. Well, we sold 35 within the first three hours!

The response was incredible! By the end of that week, we had sold another 100; in total, we ended up delivering over 200 meals to various hospitals all over Toronto.

Interestingly, most of the donations came from outside Toronto. Friends and family around the world, who, if they had been in Toronto, would have been in the ‘first week’ group of customers who show up primarily to support, jumped on this opportunity to support remotely (and generously). Bohot shukriya! 🙏

Not only did the hospital meals help health-workers, they also proved to be our lifeline.

The cost of using the kitchen every Tuesday was roughly $300 (~10 hours). Ergo, every week, we had to get orders worth at least $500 to barely cover food (20–30%) and labour (1 part-time trainee, delivery) costs. It doesn’t seem much, but, trust me, it was a struggle in June. Unable to grow sales quickly enough in downtown, we had even expanded our delivery service to include pretty much all of GTA but the additional revenue was only incremental (and not worth the angry phone calls from customers in Brampton and North York).

The upfront revenue from hospital meals turned out to be the perfect buffer for dipping (and soon to be erratic) demand. We staggered them out, delivering 15–25 meals every week depending on how many orders we got otherwise.

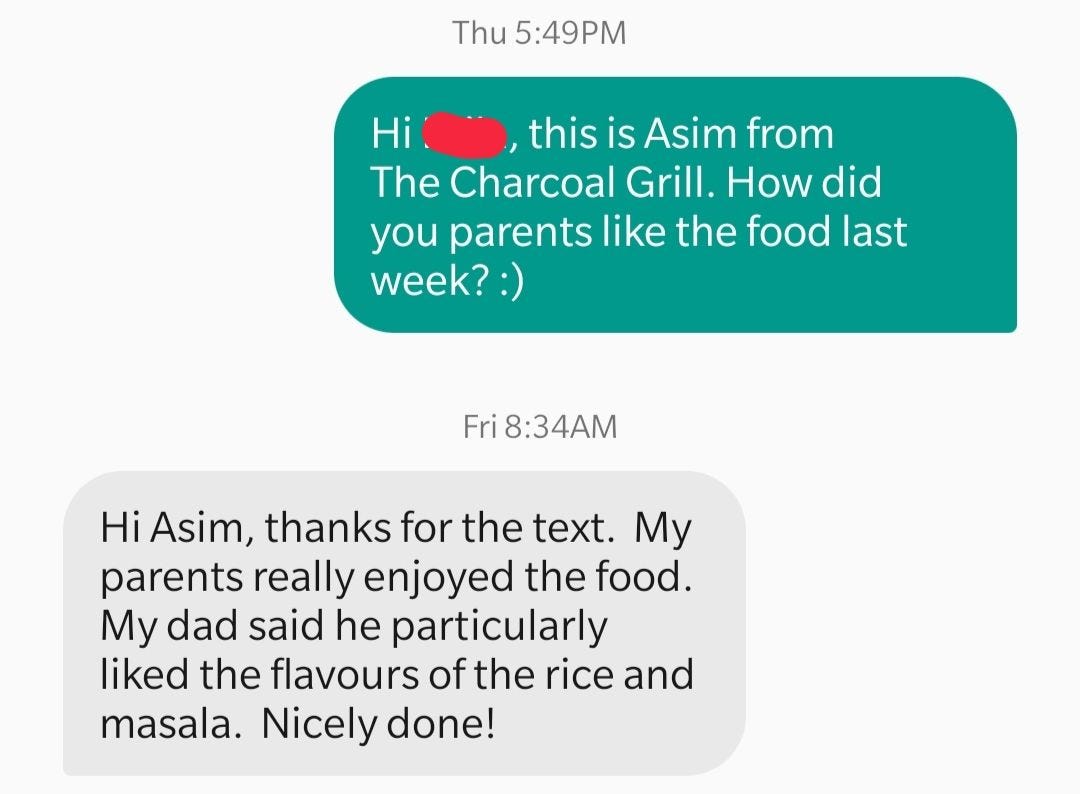

The health-workers were very kind in their feedback:

“Absolutely wonderful food! The Charcoal Grill donated to us nurses at Toronto Western Hospital to support us during this pandemic! We are so grateful for a little tasty comfort in these hard times. The staff was so friendly and kind to my team and I. Highly recommend! Excellent food and service.”

Alas, with no more tricks up our sleeve, and barely breaking even, we decided to pull the plug. Operating from a rental kitchen with no contractual commitment meant we could walk away just like that, and we did.

It’s now been seven months since that last service, eleven months since the first COVID lockdown, and exactly a year since I took the plunge.

We’re not the only casualty; according to Restaurants Canada, “since March 2020, 10,000 restaurants have closed across Canada”. While many have closed, a few brave souls have doubled down, and some new folks have entered the market.

The 30-seat restaurant we had dreamt of opening downtown last year was going to cost ~$250,000. I imagine the same would now cost half as much. But, post-vaccination, will people immediately spend as much? How long will it take for demand to approach pre-COVID levels? What about all those people that commuted into the city for work, but will now (mostly) be working from home? What about all those who have moved out of downtown altogether?

The answer is always: it depends.

Apart from your expectations from people, it depends on your risk appetite, circumstances, and abilities. In product speak, it’s no different from Cagan’s big risks. My pre-COVID self would likely (and naively) have jumped on the opportunity; knowing what I know now, I wouldn’t. Once bitten, twice shy.

When I was moving to Toronto at the end of 2019, friends and mentors had advised me to take a break for a few months. They knew how hard I worked, how long I had been working, and how badly I needed to decompress. Minahil’s full-time postdoc salary should be enough for us to survive, and we could lean on my tech savings for everything on top.

Take a break? It was something rich, privileged, typically white, people did. You know, take six months off, travel the world, find yourself. Not middle-classers like myself.

I had never taken a break in my life. Ten years earlier, when I finished college, I had intended to take some time off (from my startup), but ended up organizing TEDxLahore. One thing led to another, four incredible years flew by, and I found myself in Berkeley (for graduate school). Those two years, I could’ve taken it easy, but I couldn’t because I didn’t know how to, and I also had to work part-time (because I didn’t get the Fulbright). From there, I went to a startup where I was first loved, and a year later, unceremoniously fired. I had 30 days to find another job, and I did. And, just like that, another three and a half years flew by.

I didn’t do it.

Two weeks in, I was hanging out at the kiosk. Two weeks later, I had decided: I was going all in. And, just like that, another six months flew by.

This time around, I did take a break. In fact, I’m still on that break and, for the first time, I’m not in a rush to get back in the fast lane. Recovering from burnout has been a complicated struggle, but the journey has been absolutely transformational, both mentally and emotionally, laced with helpful new experiences. Seven months later, I’m finally beginning to feel ready to engage. Much more on that in the next article.

What’s next? I don’t know. Another startup? Probably not. Back to product management? Perhaps, but hopefully some place that isn’t selling a dollar for 80 cents. Consulting? Possibly, especially if it’s helping small businesses. Writing full-time? I wish!

If you’ve made it this far, you probably have a good sense of what I enjoy doing. What do you recommend I do next? Who should I connect with? What’s a good place for a ‘passionate generalist’ like myself? How can I help while working remotely? In fact, is there any way I can help you? Let’s talk. 😊

Until next time.